poemist

Croesus in the Comment Box

Croesus in the Comment Box

(a companion to “Poems for Money…”)

Croesus, old coin‑king,

you sit in my comment box

polishing your metaphors in gold leaf,

telling me the platform fee is “just the cost of doing art.”

But I’ve seen the gates,

how they swing only for those

with a credit card in the lock.

I’ve heard the hallow of poems

that never make it past the paywall,

their syllables still warm in the mouths

of poets who can’t afford

to spit them into the feed.

You say, “What’s a few coins for immortality?”

I say, “What’s immortality to the unheard?”

In Lagos, in La Paz, in Lahore,

there are verses that could split the sky,

but the sky here takes payment in advance.

Croesus, you measure worth in minted weight;

I measure it in the tremor of a line

that makes a stranger’s chest ache.

Your treasury is full,

but my currency is breath —

and breath should not be billed.

Still, I post what I can,

slipping lines through the cracks

between your gold‑plated rules,

hoping one will land in a reader’s hands

like contraband joy.

And if you ask me again

why I won’t pay to be heard,

I’ll tell you this:

because the richest poem I know

was written in the dust,

read aloud to the wind,

and carried farther than your coins could ever reach.

in the swelling tide

"—in the quiet tide"

an unread poem

is unwritten poetry —

ink still dreaming in the vein,

a slow current beneath the skin

where no light has yet entered.

Pages breathe in the dark,

their margins uncreased

by any gaze,

their fibres holding the faint salt

of the tree’s first rain.

They live in the quiet tide

before the pen descends,

in the pause

between heartbeat and word,

where silence folds itself

into a listening shape.

In the shadow‑scent of paper

waiting

to be touched by thought,

you can almost hear

the hush of unwoken syllables

turning in their sleep.

Some drift closer

to the shore of speech,

their edges foaming with consonants,

then slip back

into the mind’s undertow —

a retreat as deliberate as arrival.

Perfect in their unspilled form,

they are a library of ghosts,

each spine uncracked,

each title a tide‑mark

on the inner coast.

And we,

keepers of this unbroken harbour,

carry them —

the weight of what has not yet been said,

the shimmer of what may never be —

bound in the quiet tide

that moves through us,

and returns,

and moves again.

.

The Wizard of Sand

I am not the benevolent Oz, great or otherwise —

no levers behind velvet, no emerald gates to dazzle the credulous —

only the stubborn machinery of my own making,

a few cogs greased with irony,

a crank that squeaks in the key of

don’t take this too seriously,

until the hum you mistake for a hymn

becomes the wind over a toppled statue in the sand.

Once, its face wore the smirk of a ruler certain he’d outlast the sun.

The words at its base still shout about greatness —

but there’s nothing left to rule but air and grit.

Your fawn‑eyed devotion is touching,

in the way a moth’s devotion to a porch light is touching,

and just as doomed.

Look on my works, ye Mighty — and bring a broom;

the dust is winning,

and the curtain you thought was closing

was only the desert swallowing the stage.

.

in the quiet tide

The Silence Between Lines

Unread poems

are unwritten poetry —

ink still dreaming in the vein,

pages breathing in the dark,

their margins uncreased

by any gaze.

They live in the quiet tide

before the pen descends,

in the pause

between heartbeat and word,

in the shadow‑scent of paper

waiting

to be touched by thought.

Some drift closer

to the shore of speech,

then slip back

into the mind’s undertow —

perfect in their unspilled form,

a library of ghosts

bound in the quiet tide

we carry.

.

misunderstood butterflies

the scrolls stare back like a shopfront window

where the mannequins wear my metaphors,

price tags swinging from their wrists.

You didn't shake their wrists,

but I saw it nonetheless—

tags fluttering away like pale,

misunderstood butterflies.

.

the archivist

The Archivist

Breath—

caught in the rafters’ dim lattice,

a leaf turns,

seasonless.

Dust,

a pale script

unfolding in the hollow of a hand.

Spines incline—

mute elders—

their gilt a slow

constellation.

No pen,

yet the air

breaks into lines,

each pause

a door

unlatched in silence.

Volume shut—

not ending,

but the echo

of a word

never spoken.

.

the archive wing

The Archive Wing

The door is oak,

its brass plate worn to a soft blur

by decades of palms.

Inside, the air holds

the dry perfume of paper and cloth,

a faint trace of polish on the banisters.

Shelves rise like terraces,

each step a year,

each row a street in the city’s past.

Ledgers with spines like brick courses

stand shoulder to shoulder,

their titles lettered in gilt

that catches the afternoon light.

A clerk in a grey waistcoat

moves along the gallery,

his pencil ticking in the margin

of a bound minute book.

Below, a student copies

a map of the tramlines

into a ruled notebook —

ink pooling in the loops of her script.

Here, the city keeps

its own autobiography:

births and bankruptcies,

contracts and commemorations,

all pressed flat between covers.

The silence is not absence,

but the pause between sentences

in a paragraph still being written.

.

The Saga in the Hall

The Saga in the Hall

The clock in the concourse

keeps its brass face polished,

though the trains run late.

Below it, the tiled floor

is a saga of heelstrikes and scuffmarks —

polished brogues, steel‑capped boots,

heels that click like typebars.

Through the high windows,

light falls in measured squares,

as if the city itself

were an architect’s drawing.

You can almost hear

the draughtsman’s pencil

in the click and crackle of the switchboard,

the hiss and spit of the espresso machine

in the corner kiosk —

each sound another line

in the day’s unfolding chapter.

Here, commerce is not a shout

but a handshake;

industry not a furnace roar

but the steady bite of gears

in the lift shaft.

The air carries the tang of paper,

ink, and rain

that beads on overcoats —

all of it pressed into the floor’s

long memory of arrivals and departures.

We are all shareholders here —

clerks and porters,

managers and machinists —

each with a stake in the day’s

quiet transactions.

The building holds us

like a sentence holds its clauses,

each brick a word,

each scuffmark a comma,

in the city’s long,

unbroken paragraph.

.

homestead knights

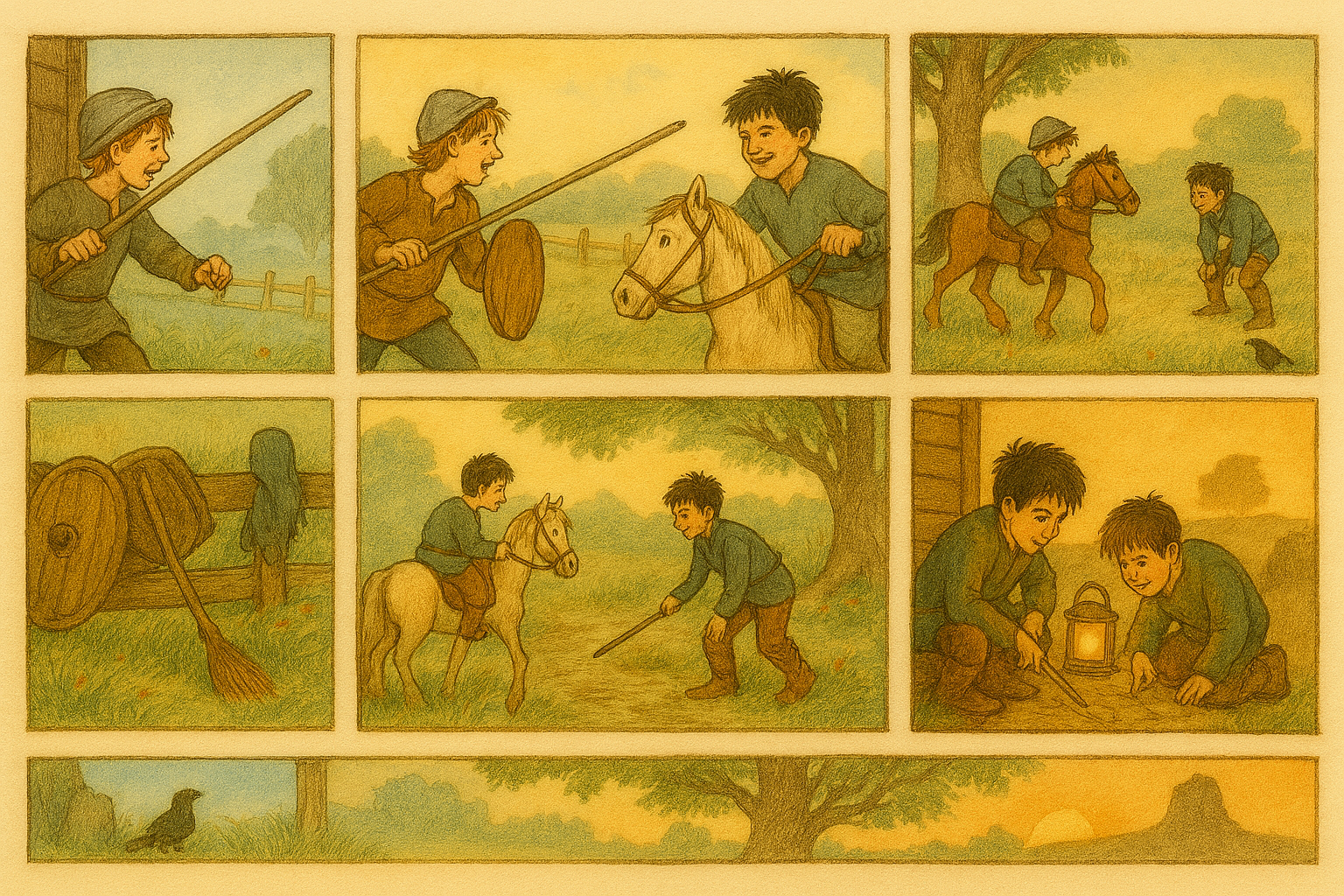

Homestead Knights

(for Arthur and Kay, before the Stone)

In the paddock’s dawn‑mist,

we joust with broom‑handles,

helmets dented from

last winter’s wood‑pile war.

Kay swears his steed

is faster than mine —

though both are milk‑cart ponies

with hay in their manes

and the patience of saints.

Our shields are feed‑bin lids,

our gauntlets, mother’s old mittens;

we ride the fence‑line

as if it were the edge of the realm.

Between chores,

we patrol the creek ford,

banish thistles from the path,

and guard the henhouse

from foxes real and imagined.

At night,

we sit on the porch steps,

boots steaming in the cool,

and plan the next day’s campaign —

whether to conquer the far paddock

or finally dare the dark of the shed.

Somewhere beyond the hill,

a stone waits in its clearing,

but for now

the kingdom is here:

two knights of the homestead,

sworn to the crown

of the rising sun.

.