redbrick

forward together

forward together

The bus doors breathe open—

a tide of shoes,

plastic bags whispering

against one another.

Someone mouths a tune to airpods.

It is enough,

for now,

to be carried forward together.

.

Devon Pan

Devon Pan

A boy with goats,

flute pressed to his lips,

breath spilling into wood—

a ribbon of sound

trembling like reeds in a river.

The goats shuffle,

a comic chorus,

yet their eyes, like his,

turn toward the woman on wheels,

her hair a banner in the salt wind.

Not Syrinx fleeing Arcadia,

but a Devon cyclist—

swift, untouchable—

her passage stirring

the same old hunger.

Pan once chased,

and Syrinx became music.

Here, the chase is only eyes:

a turning of heads,

a melody half‑formed

in the boy’s chest.

Wordsworth might have called him

“a simple child of nature,”

innocence grazing in the fields—

yet already the heart quickens,

already the world

is more than pasture.

Keats would have lingered

on the “unheard melodies” of the flute,

the sweetness of desire

that never quite arrives,

while Shelley might have named

the wind itself a piper,

scattering notes

across the restless sea.

And so the scene holds:

a boy, a flute,

goats nodding in rhythm,

a woman vanishing down the trail—

all of it ordinary,

all of it myth.

For in every gaze

that follows beauty,

in every breath

that makes music,

the old story repeats:

Pan reaching,

Syrinx escaping,

life itself singing

in the space between.

.

what was almost said

I begin with ~~certainty~~

no—only the tremor of a line,

a draft that refuses to settle.

The page offers ~~silence~~

but I write into its margins,

naming what cannot be named.

You read the ~~crossed-out~~ words

as if they were confessions,

but they are only scaffolds,

a way of showing the wound

without pointing to it.

I keep ~~erasing~~,

not to hide,

but to let you see

the ghost of what was almost said.

And when you arrive at the end,

you will find nothing resolved—

only the trace of our dialogue,

a ledger of ~~mistakes~~

that were never mistakes at all.

wrapped in ashphalt and irony

Wrapped in Asphalt and Irony

Not with a halo,

but with a steering column—

the philosopher of the absurd

meets his curtain call

in a ditch,

the Vega’s chrome twisted

like punctuation gone feral.

And yet—

he strides the void like an anime hero,

cape stitched from moth manifestos,

eyes blazing not with “Believe in yourself!”

but with the harsher creed:

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

The crowd roars,

not in faith,

but in disbelief—

that the man who taught us

to laugh at the void

was himself

laughed off the road

by contingency.

Tree or tarmac,

what’s the difference?

The absurd doesn’t care

for scenery.

It only cares

that the script ends

mid-sentence,

the ink still wet,

the ticket still unused.

So here’s the irony,

sharp enough to cut:

Camus, who crowned absurdity,

was crowned by it—

not with laurel,

but with shattered glass,

a coronation of accident.

Nevertheless—

and this is the only word

worth keeping—

his voice still declaims

through the wreckage:

not a sermon,

not a consolation,

but a dare:

to wear absurdity

as the only crown

that fits.

.

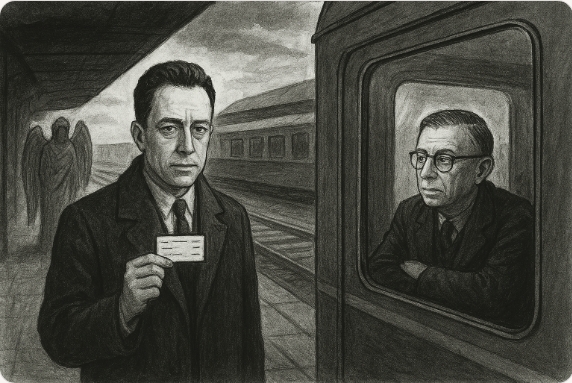

no exit, no arrival

"No Exit, No Arrival"

A Beckettian fragment in two voices

Characters:

-

Camus (on the platform, holding a ticket)

-

Sartre (inside a carriage, visible through the window)

-

Silence (offstage, but present)

(Dim light. A platform. A train stands still, doors closed.

Camus paces, ticket in hand. Sartre sits in the carriage,

staring outward. Neither moves closer.)

Camus: The train has left.

(looks at ticket)

But it has not moved.

Sartre: (through the window)

Hell is other people.

Especially when they sit too close.

Camus: I am alone.

That is worse.

Or better.

Or neither.

Sartre: There is no exit.

Only compartments.

And coughs.

Camus: I missed my ride.

Perhaps that was the ride.

Perhaps this is the punishment.

Sartre: Punishment?

No.

Merely company.

Which is worse.

(Silence enters. Both men look at it.

Silence says nothing. They nod.)

Camus: One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Sartre: One must imagine the carriage full.

Forever.

(The train whistle blows. Nothing moves.

Lights dim. Curtain does not fall.)

.

parable of two wrecks

Parable of Two Wrecks

Dean’s collision left a boy in a Ford,

haunted by silence,

living decades with the weight of a single instant,

his name footnoted, his breath unremarked.

Camus’s crash left a friend in the driver’s seat,

carried off days later,

as if absurdity refused to leave witnesses—

the philosopher and his publisher

bound together in the same unfinished sentence.

So one man lived too long with history’s hush,

another died too soon in its echo.

And the parable is this:

fate spares and fate consumes,

but always without reason,

always with perfect irony.

.

.

crowned by werckage

Crowned by Wreckage

He faced the void like a cartoon hero,

not with the easy cry of “Believe in yourself!”

but the harsher creed: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

The moths bore his manifestos into flame,

while history yawned, shelving him beside

pamphlets on extinct animals.

And then—tree or tarmac, it mattered little—

the absurd he crowned crowned him in return:

not laurel, but twisted chrome and shattered glass.

The philosopher of chance was felled by chance,

his last ticket unused, his last line unfinished—

a coronation written in wreckage.

.

weapons of mass distraction

weapons of mass distraction

Screens glow like altars.

We kneel, thumbs twitching

prayers to gods of noise.

The loudest silence is

the one we scroll past.

Billboards bloom

like invasive flowers,

their petals of neon

masking the stars.

We are armed not with rifles,

but with endless feeds,

notifications detonating

in the pocket. The war is

not for land, but for attention.

Somewhere, a child waits for

a story that is not interrupted

by a ringtone.

The weapon is simple:

keep you from yourself.

.